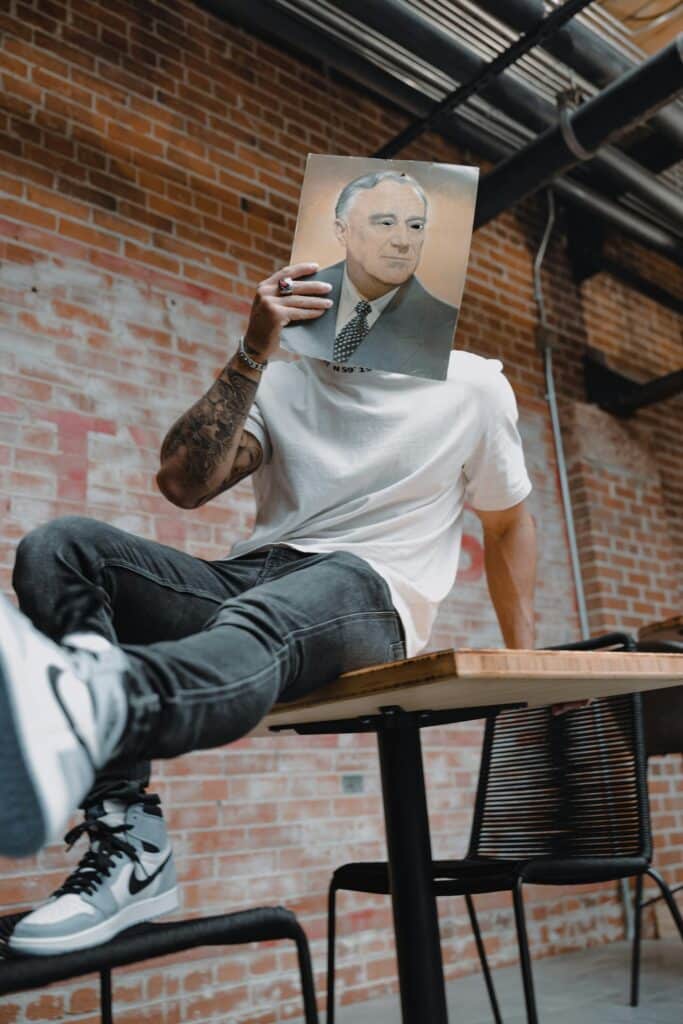

The Danish government has recently proposed amendments to the Danish Copyright Act that will give individuals rights over their personal and/or physical characteristics where these characteristics are incorporated into computer generated content – so called AI “deepfakes.”

AI deepfakes are an area of significant concern. Recent advancements in AI technology have given anyone with access to a computer the tools to create extremely realistic images, video and audio content of other people without their consent.

Denmark’s proposal represents a further attempt to give individuals control over how their image is used by third parties deploying AI technologies. It builds on existing law in Europe, Britain and the USA.

In this blog, we consider what the proposal entails. As well as this, we consider what the current state of the law is in the UK and other jurisdictions around deepfakes.

The Danish proposals to tackle deepfakes

The Danish legislative proposal (here, in Danish) contains two key provisions that will provide protections to individuals who find that their characteristics are being used to create AI deepfakes.

Individual protection

The first amendment to the Danish Copyright Act states (machine translation):

»Protection against realistic digitally generated imitations of personal characteristics

[Subsection 1]. Realistic digitally generated imitations of a natural person’s personal, physical

characteristics may not be made available to the public without the consent of the person imitated.

Subsection 2. Subsection 1 does not include imitations that are mainly expressions of caricature, satire, parody, pastiche, criticism of power, criticism of society, etc., unless the imitation constitutes misinformation that can specifically cause serious harm to the rights or essential interests of others.

Subsection 3. The protection in subsection 1 shall last until 50 years have elapsed after the year of death of the person imitated.

This section, in short, provides a limited form of personality right that all individuals (anywhere in the world) can enforce against third parties within Denmark that publish deepfakes comprised of characteristics of the individual.

A personality right is a type of property right, similar to copyright or other forms of intellectual property rights. As a property right, an individual can stop others from using that property without their consent in certain circumstances. Under the proposal, the personality right is tightly curtailed:

- It relates only to ‘realistic digitally generated imitations’ of a person – so in other words an individual would not have the same personality right in respect of an actual image of them published by a newspaper (for example).

- It contains various carve outs: ‘caricature, satire, parody, pastiche, criticism of power, criticism of society.’ A satirical deepfake would be safe from the individual’s enforcement of their property right.

- Those carve outs have their own restrictions. A satire that constitutes misinformation that could cause serious harm to the individual or the public would be actionable.

This is a useful step forward for individuals looking to stop the proliferation of deepfakes containing their characteristics.

Importantly, the wording of the proposed changes explicitly state that the personality right covers any deepfake – not just deepfakes that are plainly harmful (e.g. sexual imagery published without consent, fraud or blackmail).

This goes further than the general European position and the law in the UK and the US. We discuss the differences further below.

Artistic protection

Rights of artists are already protected by the Danish Copyright Act. For example, a film producer would have the right to prevent unauthorised copies of their work from being distributed.

The proposal would extend these various rights to cover (machine translation): ‘digital realistic imitations of performances by performing artists or of artistic achievements by artists.’

In short, deepfakes which are not exact copies of, for example, a video but are essentially the same work would be treated as if they were exact copies. This should also cover AI-generated audio of musicians and singers – a key expansion of copyright law against what is the general position in Europe and the UK.

The proposal would give artists and other intellectual property rights holders an extremely useful tool to stop users of AI tools from generating content and passing it off as their own work.

Current international laws against deepfakes

The Danish proposal is notable as it provides a useful recent example about how governments are looking to tackle deepfakes. The pace of AI capability still continues to outstrip legislative efforts to curb its use – the Danish Government is offering a potential way forward that could keep pace with that change.

Examples of legislative control over deepfakes, and their limitations, include the following.

EU

GDPR: Under the GDPR, individuals have rights over the use of their personal data. Personal data is defined as ‘any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person.’ Sufficiently accurate and/or realistic deepfakes would constitute personal data. Individuals can, amongst other things, request that personal data is erased. But there are limitations to this right, and in a general sense the GDPR is not always sufficient to tackle deepfakes given the carve outs it gives organisations to resist the rights of individual.

EU AI Act: the EU AI Act requires that AI deepfakes are labelled as such, increasing transparency. But the EU AI Act does not itself regulate the publication of deepfakes by third parties.

Digital Services Act (DSA): the DSA places obligations on online platforms to remove harmful content, which could include deepfakes (e.g. where a deepfake represented an intimate image). Not all organisations would qualify as an online platform under the DSA, and the DSA does not generally apply to individuals. Of course, not all deepfakes are inherently “harmful” within the meaning of the DSA, even if they are certainly unwanted.

Personality rights: across the EU there is a patchwork of member state law that provides forms of personality right. Most of these relate to the privacy of the individual, as opposed to controlling the use (commercial or otherwise) of one’s personality. In certain circumstances laws against defamation or derogatory treatment could be used to tackle deepfakes. The totality of this means that preventing the publication of deepfakes is down to the content of the deepfake itself.

UK

UK GDPR: the UK’s form of the GDPR, the UK GDPR would operate in the same way as the EU GDPR. The UK GDPR therefore contains much of the same limitations.

Online Safety Act 2023: the UK’s Online Safety Act 2023 amended the Sexual Offences Act 2003 to criminalise the publication of intimate images without consent – including deepfake images. This did not include the criminalisation of creating such images. That was dealt with in the Data (Use and Access) Act 2025, which criminalises the creation of intimate deepfakes of individuals (and the commissioning of them). This UK legislation is useful to combat one of the worst forms of AI deepfakes, but in relation to other harms or unwanted images it is well short of the Danish proposal.

Personality rights: the UK is notable for not enshrining a clear personality right in law. Other than the rights that relate to privacy and defamation, individuals are normally only protected in the context of ‘passing off’ – where a third party uses a person’s image for commercial gain without consent. This would not protect most people, and again the protection requires a commercial context.

USA

State/federal privacy laws: privacy law in the US is a patchwork. Certain jurisdictions, such as California, have privacy laws that are broadly comparable to the GDPR – with the same limitations.

Take It Down Act: similar to the DSA and the Online Safety Act 2023, recent federal law will oblige online platforms to remove intimate images (including deepfake images) within 48 hours. Certain states, such as Texas, have similar protections around this particular type of harmful deepfake.

Personality rights: various states in the US have comprehensive personality rights, preventing others from using the personality of individuals without consent for commercial gain. Again, because of the commercial context here, it is unlikely to be a relevant right in respect of most deepfakes.

Concluding thoughts

Denmark’s proposed reforms are a welcome evolution in the legal landscape around AI and deepfakes. By offering a relatively novel mechanism for individuals to assert control over the digital replication of their identity, it is to be hoped that other countries take note and widen the scope of their existing legislative tools to counteract harmful deepfakes.

At EM Law, we are experts at AI, data privacy and related issues. If you have any questions about deepfakes or your rights in respect of any deepfakes that have been published about you, please do not hesitate to contact us here.